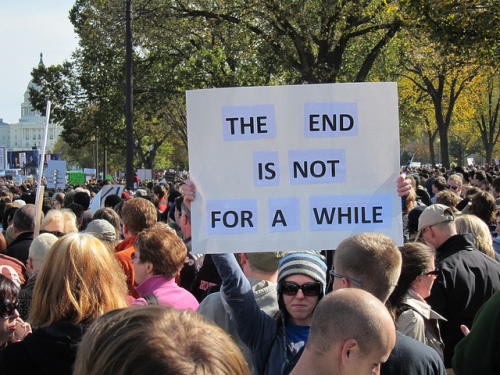

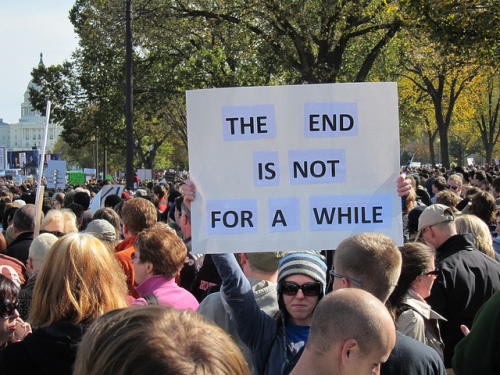

I preached about prophecy this morning at Mass. I was provoked (I won’t say inspired) by the whole non-Mayan non-apocalypse non-event that was Friday 21 December 2012. It shows how even an urban myth that becomes an uber-trending news story can stimulate some helpful reflection.

Part of the attraction of the ‘crazy religious people waiting for the end of time’ story is that it seems to pit crazy religious people against un-crazy scientific people. But one of my small points this morning was that the desire to believe in prophecy, at least in its slightly over-simplified meaning of ‘telling you something that is going to happen in the future’, is actually one with the scientific instinct. It’s a longing to believe that everything makes sense, that everything happens for a reason, that the future is (through some very mysterious processes of futurology) pre-determined and knowable.

The belief that the world as a whole and every detail within it is meaningful, and that in theory this meaning can be discovered, is a belief that shapes both the worst excesses of superstition and the best endeavours of science. We don’t want to believe that everything is simply chaos; and in fact we have good reasons to think (if our epistemology is sound) that there is a fundamental order to the universe, and that our minds can gradually discover that order.

This hunger for order drives the scientist and the Mayan apocalypse seeker. It also drives the conspiracy theorist, as portrayed so well by Don DeLillo in his novel Underworld, who can’t conceive that a world-changing event like the assassination of JFK or the death of Princess Diana could have been caused by something as banal as a lone gunman or a tragic accident.

Yes, there are crazy prophecies; and there are non-prophecies (it seems that not even the Mayans really believed that this one was coming). But there are true prophecies as well, where God has spoken into history, and promised or predicted (perhaps they mean the same thing from the perspective of eternity) that something would happen in the future.

We see two of them in the scriptures today. First, seven hundred years before the birth of Christ, the prophet Micah promising that a leader would be born in Bethlehem; one who would shepherd God’s people, unite and strengthen them, and bring them lasting security and peace. And second, the Angel Gabriel appearing to Mary, telling her that her cousin Elizabeth was with child in her old age. No wonder she went to visit Elizabeth with such haste; partly to share her joy at the Incarnation, but partly to see with her own eyes a truth she could only hold in faith up to that point.

Prophecy used to be such an important part of the Judeo-Christian imagination. It reminded us that all things – including the course of history – are in God’s providential hands; it showed us his power and his wisdom; it was a sign of his care for us and of our own dignity – that he would speak to us and involve us in the unfolding of his plans; and it was above all a powerful indication of his faithfulness to us, and our need and our duty to trust him because of the objective signs that he has given us in history, as well as the personal signs he has given in our own life story.

I think we have lost our confidence in all this, for all sorts of reasons: historical criticism of the Bible; a loss of the sense of the supernatural; the shift from a historical religion to a personal spirituality, from an objectively founded faith to one based on inner subjective experience; and many others.

Some of the scepticism about prophecy is justified, and it reflects a whole different world view. But some of it is not – it is an unscientific narrowing of the human mind: to think that there is no fundamental order to the universe or to human existence; that God the creator is unable to guide his creation or direct the events of history; that he cannot in his infinite wisdom know what he ‘is’ doing or what he ‘will’ do; or that he cannot share his knowledge of what he will do through revelation in general and through the prophetic word in particular.

This is our faith as Christians, that these things are possible for God. And it’s not just a credulous, superstitious faith; it’s based on our rational understanding of what it means for there to be a universe at all, and our conclusion that some transcendent power and wisdom must lie behind this creation, a power that we have discovered – in the Old Testament and ultimately in Jesus Christ – to be personal and loving.

Prophecy still matters. The fact that God has spoken through the prophets and fulfilled his promises is one of the factors that allows us to believe with more confidence. It may not provide a proof that what we believe is true, but it is a good stimulus to belief, and an ongoing support.

This is how the First Vatican Council put it, a teaching that is as relevant today as it was in the nineteenth century (Dei Filius, Chapter 3):

4. Nevertheless, in order that the submission of our faith should be in accordance with reason, it was God’s will that there should be linked to the internal assistance of the Holy Spirit external indications of his revelation, that is to say divine acts, and first and foremost miracles and prophecies, which clearly demonstrating as they do the omnipotence and infinite knowledge of God, are the most certain signs of revelation and are suited to the understanding of all.

5. Hence Moses and the prophets, and especially Christ our lord himself, worked many absolutely clear miracles and delivered prophecies; while of the apostles we read: And they went forth and preached every, while the Lord worked with them and confirmed the message by the signs that attended it [18]. Again it is written: We have the prophetic word made more sure; you will do well to pay attention to this as to a lamp shining in a dark place [19].

6. Now, although the assent of faith is by no means a blind movement of the mind, yet no one can accept the gospel preaching in the way that is necessary for achieving salvation without the inspiration and illumination of the Holy Spirit, who gives to all facility in accepting and believing the truth [20].

7. And so faith in itself, even though it may not work through charity, is a gift of God, and its operation is a work belonging to the order of salvation, in that a person yields true obedience to God himself when he accepts and collaborates with his grace which he could have rejected.

Read Full Post »

![World Youth Day 2008 Concert (#458) by Christopher Chan [CCL] http://www.flickr.com/photos/chanc/2683632239/in/set-72157600042025565/ World Youth Day 2008 Concert (#458) by Christopher Chan.](https://i0.wp.com/farm4.static.flickr.com/3081/2683632239_c9fe3c3f8f.jpg)

![Thank you God! by Daniel Y Go [CCL] at http://www.flickr.com/photos/danielygo/3949411671/ Thank You God! by Daniel Y. Go.](https://i0.wp.com/farm4.static.flickr.com/3432/3949411671_141bbcf1e6.jpg)